Very often when my children ask me for something that they know they aren’t likely to get, I will try to lighten the moment by asking them, “Do you want the short answer or the long answer?” The short answer, of course, is “no.” The long answer explains why.

For many within the fundamentalist movement the question “Are you a fundamentalist?” needs the long answer. The reason for this is that fundamentalism is a nuanced web of historical, theological, and political complexities. You could throw into that mix a few prominent personalities.

The last thirty years have seen significant change in fundamentalist circles. David Beale, historian at Bob Jones University, identifies this change as the “neo-fundamentalist defection into broad evangelicalism” which he says began about 1970. This defection has increased exponentially in the last ten years.

The last of the “fighting fundamentalist” leaders has gone on to glory and the movement is struggling to remain intact. Many more senior fundamentalists are struggling to move into a post-Christian context and the younger generation has no interest in going back to rehash old wars (the battle-lines have shifted). Many are thinking through the issues, some significant fundamentalists are writing about the current difficulties, and some are trying to reform the movement, but large numbers are leaving. This past year three key fundamentalist schools were forced to close their doors. Fundamentalism is in decline, if it has not already expired. Those colleges that have survived have had to make substantial changes—perhaps too little too late.

The answer to the question “Are you a fundamentalist?” still poses problems for many who remain within the movement. Their responses balance gingerly on the difference between what fundamentalism was in its essential and historical purpose and what fundamentalism became as a major politico-religious movement. Let’s start with a bit of history.

To understand fundamentalism you need to know that it was a response to theological liberalism. Liberalism was the theological revolution that began in Germany in the early 1800s, spread through Europe, and made its way into the seminaries and universities of America. By 1900, as Eugene Osterhaven pointed out, “the transition had virtually been completed and the Liberal era in American theology had arrived.” Liberalism was an anti-supernatural movement focused on a social gospel. It denied the authority of Scripture and other core doctrines of the Christian faith. It adopted a higher-critical approach to the text of Scripture, which worked on the premise that the Scriptures were mere human productions. Liberalism was—and is—an apostate system, and those who opposed it became known as fundamentalists because they held to the truths of Scripture which were considered fundamental to orthodox faith.

Liberalism affected every denomination and each denomination dealt with it in different ways. Some were swallowed up in its perceived wisdom and scientific advancement, so called. Others quietly weathered the storm or separated, and many of these still exist today as conservative evangelical independent churches or smaller denominations. The Plymouth Brethren, for example, isolated themselves from the other denominations and were unaffected by the theological discussion despite the fact that their brand of dispensationalism was very influential on early fundamentalist thinking. The Plymouth Brethren movement was a significant part of conservative Christianity and some historians believe that because they isolated themselves from a broader church life in England fundamentalism never gained momentum in that country.

In North America, however, fundamentalism developed into a major ecclesiastical movement that spanned a number of different denominations. The beginning of fundamentalism in America goes back to the late 1800s with a “proto-fundamentalism” (circa 1878–1914), which was heavily influenced by dispensational theology and prophetic conferences.

The tipping point, however, came in the mid 1920s when, after years of frustration over the double-speak of liberals, fundamentalism was forced to adopt a decidedly militant approach. The year to remember is 1927. That is when the mainline church that had been taking a defensive position took an actively offensive position and the first denominational splits took place. New churches were formed and also in that year a number of fundamentalist educational institutions were established across America and Canada. Fundamentalism had changed from a peaceful movement within the mainline churches to a theological war machine that took no prisoners.

The only other country in the world where a fundamentalist movement developed was in Northern Ireland. Again, 1927 was a key year. Modernism had been making its voice heard for some time. For twenty years Rev. James Hunter had made numerous protests against the Presbyterian Church of Ireland and its close links with the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

In 1925 Jim Grier, a young student from Donegal, Northern Ireland, returned home after two years in Princeton Seminary, in the U.S. As he settled into his final year of preparation for the ministry in the Presbyterian Church in Ireland (PCI) he found himself debating openly with the professors in Union College, Belfast. In December of 1925 Jim Grier sought counsel from Rev. James Hunter and from this point the two men became close allies in the cause against liberalism in the PCI.

In 1927 Prof. J. E. Davey of Union College was tried for heresy and acquitted. This was too much for Hunter and Grier so they left the PCI and formed the Irish Evangelical Church (it later became the Evangelical Presbyterian Church). Grier had already been exposed to this controversy in America and his friendship with J. Gresham Machen—an important figure in the stand for truth in America—was influential in this early break from the PCI. Machen visited Belfast that same year. As in America this early break from the PCI was moderated by a thoughtful and non-sectarian approach.

Militant fundamentalism, as we know it, did not come to Northern Ireland until the early 1950s when Rev. Ian Paisley pursued a relationship with his American counterparts after the forming of the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster.

By the mid 1960s in Northern Ireland fundamentalism had taken on the characteristics of a movement, albeit on a more limited scale (mostly among Free Presbyterians) and closely linked with the political struggle of that country (politics also played a role in America and to a lesser degree in Canada). The impetus for fundamentalism developing as a movement in Northern Ireland came with the imprisonment of Dr. Paisley and two of his associates for protesting at the General Assembly of the Irish Presbyterian Church.

Although the Free Presbyterian Church had begun in 1951 there was little growth in the new denomination prior to 1966; only twelve churches had been established in fifteen years. During and after the 1966 imprisonment, rallies were organized across the country and interest in Paisley’s movement gained momentum. Those churches established during or immediately after the three-month imprisonment became known as “the prison churches.” In less than two years the number of congregations doubled and Paisley’s new Martyrs’ Memorial Church, seating 2500, was under construction. “Paisleyites,” as they became known, were finding their feet and making their voice heard all over the country.

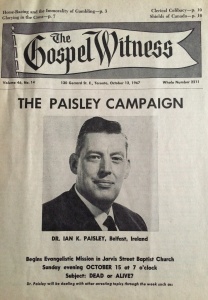

The 1966 imprisonment raised the Paisley name to celebrity status not only in Northern Ireland but also in North America. At least three fundamentalist periodicals picked up the imprisonment story: in Canada, The Gospel Witness of T. T. Shields’ fame, and in America, John R. Rice’s The Sword of the Lord and Carl McIntire’s The Christian Beacon. The following year Paisley embarked on a tour of the U.S. and Canada, beginning in Pennsylvania at the end of March where he was met at the Philadelphia International Airport by “several hundred hymn-singing supporters.” After meetings in the Bible Presbyterian Church he moved on to the annual Bible Conference at Bob Jones University. His name appeared in many local newspapers and was aired on radio programs across the nation announcing his meetings. In the October 12th 1967 edition of The Gospel Witness a portrait of the middle-aged Paisley covered the front page announcing a series of meetings that took him from the Maritimes in the east to Vancouver on the West Coast. Paisley was now accepted into the fundamentalist “Hall of Fame” with honors.

The 1966 imprisonment raised the Paisley name to celebrity status not only in Northern Ireland but also in North America. At least three fundamentalist periodicals picked up the imprisonment story: in Canada, The Gospel Witness of T. T. Shields’ fame, and in America, John R. Rice’s The Sword of the Lord and Carl McIntire’s The Christian Beacon. The following year Paisley embarked on a tour of the U.S. and Canada, beginning in Pennsylvania at the end of March where he was met at the Philadelphia International Airport by “several hundred hymn-singing supporters.” After meetings in the Bible Presbyterian Church he moved on to the annual Bible Conference at Bob Jones University. His name appeared in many local newspapers and was aired on radio programs across the nation announcing his meetings. In the October 12th 1967 edition of The Gospel Witness a portrait of the middle-aged Paisley covered the front page announcing a series of meetings that took him from the Maritimes in the east to Vancouver on the West Coast. Paisley was now accepted into the fundamentalist “Hall of Fame” with honors.

This brief survey of the movement ties fundamentalism together in three countries: America, Canada, and Northern Ireland. As I stated before there was no fundamentalist movement outside these three countries. This is an important observation, as one Canadian historian poignantly remarked: “There was no fundamentalist movement in England, and there is no church in England to speak of.” Apart from a few small and struggling churches, England has no unified evangelical voice.

Early fundamentalism was effective. Whether you agree with other aspects of the movement or not, this much is clear, as Iain H. Murray wrote: “Fundamentalism … cannot be easily ignored.” Both Northern Ireland and North America enjoy the benefits of evangelical truth that can be traced directly to the fundamentalist movement. This gives some perspective to the movement and, in my opinion, should generate not a little gratitude for the stand that the early fundamentalists took for the “faith once delivered.”

There were, of course, fundamentalists in England. Spurgeon separated from the Baptist Union in 1887 in what was called the “Down Grade Controversy.” What is significant about the Down Grade controversy, however, is that it had no lasting effect. Despite the fact that Spurgeon was so well received in the Baptist Union when he first came to London in 1854, he had little influence in the Union when liberalism appeared. There was little influence also from the American fundamentalists who succeeded Mr. Spurgeon in Metropolitan Tabernacle: A. T. Pierson (1891–1893) and A. C. Dixon (1911–1919).

By 1934 at the centenary celebrations of Spurgeon’s birth even Spurgeon’s friends in conservative Baptist circles were embarrassed with the controversy and indeed implied that Spurgeon was to blame for leaving the Baptist Union.

There were other attempts in England to organize a militant anti-liberal movement, such as that by John W. Thomas and the Baptist Bible Union, and E. J. Poole-Connor’s fellowship of Independent Churches (1922). None of these movements gained significant traction, and a number of studies have suggested a few fascinating reasons. One suggestion is that the English fundamentalists—Dr. Martyn Lloyd-Jones, J. I. Packer, and John R. W. Stott, to name a few—were “moderate.” There were others not so moderate and even some closely associated with the American movement, but despite this, no movement as such formed in England and the Northern Ireland movement had no real influence on mainland Britain.

Rather than call for separation, as the fundamentalists did, Lloyd-Jones, in the 1950s and 60s, called for an “evangelical unity based only on the gospel.” Interestingly, today Lloyd-Jones’ influence in England is limited, although he is regarded with tremendous respect in the wider Reformed church, and deservedly so.

In the early 1970s Lloyd-Jones changed his view on church unity and separation. His biographer points out that his “scope was deliberately narrowed” and he no longer “looked for a broad influence.” Evidently Lloyd-Jones realized, as the fundamentalists had been saying all along, that the way forward was for the “minority to stand fast and, in so doing, prepare the way to brighter days.”

In the March 2006 edition of Tabletalk R. C. Sproul, Jr., wrote an article called “Our Fundamentalist Betters.” In that article he recognized the debt that the evangelical church owes to the fundamentalists. Sproul says, “The fundamentalists of the last century were … scorned. And for that they earned the praise of Jesus.” The “contendings and tirades,” to quote Lloyd-Jones, paid off and preserved the strong evangelical presence that we enjoy today.

Reformed and evangelical churches in Northern Ireland and in North America can thank the fundamentalists for standing up and screaming “Foul!” when others kept silent, recoiled into their own comfortable constituency, or focused on the positives hoping the negatives would disappear. Although very much a voice in the wilderness, (e.g., less than 1% of the Protestant population in N. I.), it cannot be ignored that the “religious right” has been an active political and spiritual force in America, Canada, and in Northern Ireland.

The fundamentalist movement had many and serious faults, which I hope to address in another article. There was much that the movement failed to achieve within its own ranks, but it must be recognized that the noise of battle made others sit up and listen and that it “prepared the way to brighter days.” Conservative evangelicals are enjoying those “better days” today.

Leave A Comment